Adam Smith

For such a famously humble man, Adam Smith left a complicated legacy. A friend and student of David Hume and Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith took it upon himself to inquire upon the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations since the wealth of a nation had so much obvious bearing upon the quality of life of its inhabitants.

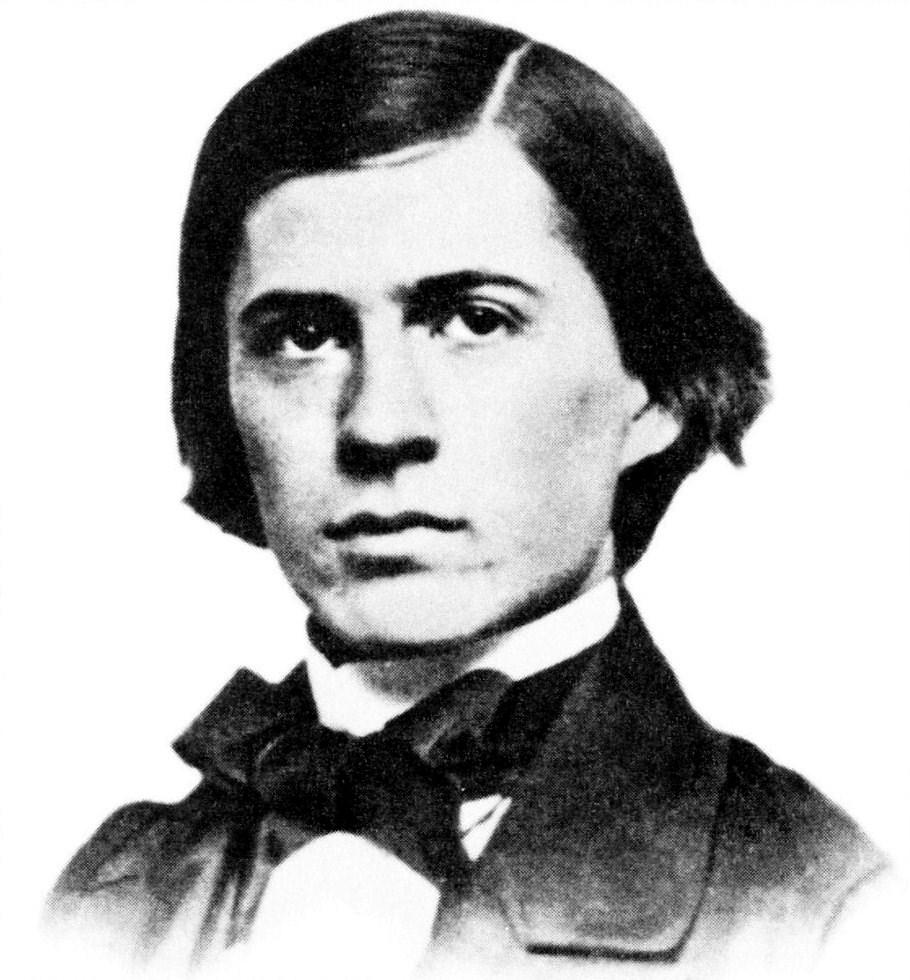

David Ricardo

Within Wealth Of Nations, there are mixed up two very different forms of analysis which are not easily reconciled. On the one hand, there was analysis of the "state of nature" and "stationary state", both concepts learned from Hume. In these states, there was a labor theory of value and life was static. On the other hand, there was the dynamic life of growth that he saw in England and America, where he applied a more lax "Supply and Demand" analysis. In so doing, Smith was the father of both classical economics as developed by Ricardo and neoclassical economics as developed by Alfred Marshall.

Thomas Malthus

The stationary state is one in which land and capital have been distributed and innovation is low enough to be negligible. It is a very unpleasant place: "Though the wealth of a country should be very great, yet if it has been long stationary, we must not expect to find the wages of labour very high in it.". Without movement or innovation, capitalism would then take on many of the aspects of feudalism - Adam Smith examined the late Chinese Empire as a model stationary state.

Without innovation, wages would become a decreasing function of population. This state is often now called "Malthusian", even though it was first developed by Smith and its reality and immanence was not questioned by any classical economist (including Marx). Ricardo (and Malthus) differed from Marx in their predictions about the stability of the stationary state. All agreed that it was, in Marx's famous words, the center of gravity about which capitalist prices moved. Ricardo and Malthus believed that it would be stable, and that life would be horrible forever.

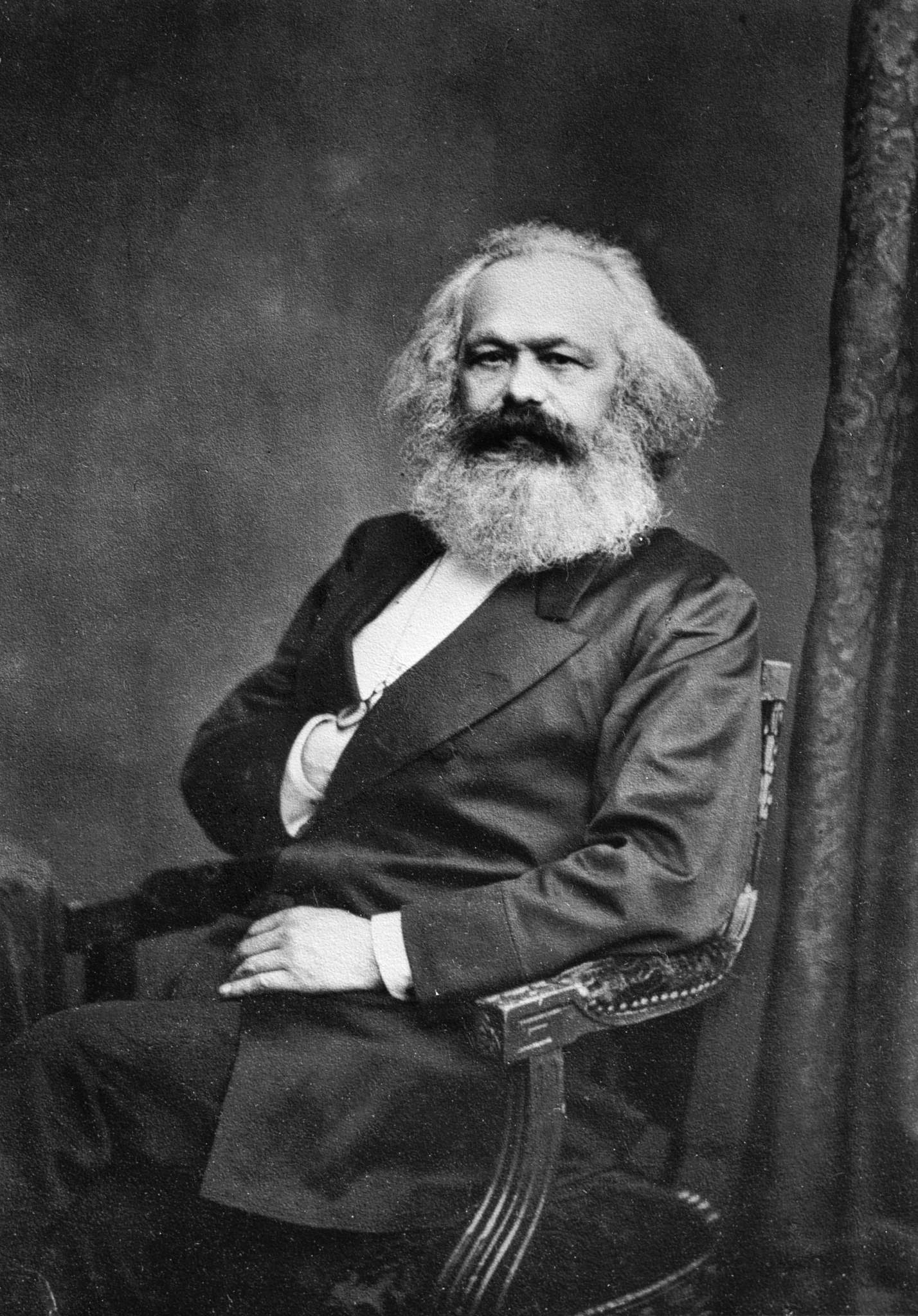

Karl Marx

I promised in a previous post to explain Marx. This can now be done. The price of a good or service (I will say "task") in the stationary state is called by Marx its "value" and by Adam Smith its "natural price". Again, in the stationary state technique, resources and factor cost is fixed for each firm. It is easily seen that in this case, aggregate output is solely a function of the quantity of employees hired. In addition, with fixed technology, a given level of employment for a given task fixes the return for that task. Since the price of a task is simply the ratio of the total income each unit rewards to the count of units, price in the stationary state is solely a function of labor allocation. This is the "labor theory of value" stated in a fashion both simple and acceptable to anyone.

One can go further than this. In the stationary state, each child born is born to a given task. That, under capitalism, laborers beget laborers, and Irishmen Irishmen was unquestioned by Marx (he despised it, which is different than questioning its truth). This means that price was, in fact, a function of total population. One could not ask for a stronger labor theory of value than the value of every task being solely a function of total population!

Marx went so far as propose a theory that part of total population was left idle in the stationary state, what he called "reserve army of labor". This is no small achievement, it was probably the first quantitative theory of unemployment!

Leon Walras

What about the neoclassical economists? They fit into this scheme just fine. Let me explain. I think it is likely that the Smith-Ricardo-Malthus description of the stationary state that culminated in Marx is correct. Karl Marx also insisted constantly throughout his life (in all three volumes of Capital, for instance), that supply and demand determines the fluctuation of prices. (Wage Labour and Capital suggest that he had in mind something like a cobweb model in mind, but that is a digression)

What does this mean? From a mathematical point of view, Marx's thoughts are a special case. It holds when land, technique, resources and factor cost are all fixed and laborers will be distributed in a unique way between different industries. Marx would, if he were not in a nasty mood, agree whole heartedly! Marx's point is that the Ricardo-Malthus analysis (he would be upset to see Malthus there) is the economically central case. Not the more mathematically general or logically most important. Marx believed that this was a globally asymptotically stable equilibrium, the only results of the economic laws of gravity was to approach it. This is a perfectly logically consistent way of viewing the world. Marx would be pleased with his "critic" who would point out that we can also think of other societies that have different equilbria - that's why Marx was a communist after all!

Robert Solow

Recall that I said Adam Smith had two legacies. The classical economists expanded on his Humean analysis of two possible static equilibrium. But there was another, less developed but more original side to Adam Smith. This was the Adam Smith of supply and demand; the Adam Smith that noticed that England, the United States and probably all of Europe is nowhere close to a stationary state. The Adam Smith who was perfectly capable of noticing that demand curves slope down.

The early neoclassical models of Cournot, Alfred Marshal and Leon Walras were one period models. As a result, their relationship with the theories of Ricardo, Malthus and Marx were terribly unclear. Austrian economists had a particular interest in extending these models to many period, however this line of thought had its greatest culmination in an American economist - Irving Fisher. However, this only increased the murkiness of the relationship of neoclassical models to the Marxian stationary state. The reason was that the Fisher/Austrian models had "periods of time" (and therefore an interest rate), but no growth per se.

The first theory of stable, exogenous growth was proposed by Robert Solow and Trevor Swan in 1956. (I will ignore endogenous growth, which is irrelevant to Marx) Possibly the best introduction to the model and neoclassical thinking about it is here, but Solow's original paper is excellent. Finally we had a model that could accept changes in the supply of labor and the intensity of capital! The analysis of this model may seem to lead to a very Marx-esque solution, asymptotically only technical change produces growth. Since - as noted above - in the long run of Marx there is no innovation, this is okay. But as a matter of fact, this model, and virtually all modern growth models, propose a path of steady growth with no end in sight! There is no cap on the population, no steady state wage stagnation and capital can be accumulated unlimitedly! There are Solow models with fixed inputs, such as land, but the possibility of unlimited growth is baked into the analysis.

How is this possible? Where Marx set economic growth to zero in the steady state, Solow looks to a more economic and less mathematical definition. An economy's growth is called "balanced" if its capital stock divided by its total output is constant. That means each machine is asked to stamp goods at only a certain, reasonable rate. Holding a ratio still means that the numerator and denominator go to infinity - as long as they do so at the same rate. What makes Solow's analysis brilliant is that he is able to find mathematical meaning to that fact and get a quantitative model out of it! The result is clear: economic center of gravity is at infinity, and value in Marx's sense is simply unimportant.

Marx (and his hated enemy, Malthus) would think this analysis is foolish. The crash is going to come - either in population (Malthus) or capital (Marx). This brings us to the sunset of classical economics. As the years and generations - much more than a century - has gone by, this stylized fact and great prediction has failed and failed again. I don't say that the day is over for it, but its light is going out...