The advantage of 1) is that since it is my own experience, I can recall - or fabricate - every detail the best. It's the most personal, and even minor real experience can be worth a metric ton of high-carbon reflected life. The disadvantage is that at the time I was living a pretty dull and comfortable early teen life. I would have hated to have to live with bombs falling on my head, but it would certainly made my decision to watch cartoons late at night in some way interesting.

The original Adult Swim line-up

I can only remember the decision to watch Adult Swim in an unclear way. It was conscious, though I don't remember where I found out there was going to be a thing called Adult Swim. Possibly/probably a commercial. I was a fan of the Williams Street show Space Ghost Coast To Coast from the first moment I heard the Sonny Sharrock theme. Revisiting that, I realized that it was a lot more hit-and-miss than I thought. It's obvious in the first season or so they didn't feel comfortable abandoning the "talk show" element for little things like "comedy". But eventually, they'd abandon it for garden clippings just to have the excuse. They did a stupid little special Brak Presents The Brak Show Starring Brak, but I could forgive them for that. Besides, now they were going to have their own block! I had to check that out. In retrospect, it's obvious that the line up wasn't supposed to have any anime on it. It was 84% comedy, and mostly Williams Street originals. Besides, that was what we had Toonami for. But Bebop didn't fit on the old Toonami, it's a show that needed night. Jazz is night music. Bebop is a night show.

Maybe a lot of the famous Williams Street animosity to anime comes from that feeling that they gave anime an inch with Bebop, and they took a mile... Oh hell, for old times sake, let's go through the line-up as I saw it.

Home Movies

I didn't see home movies when it was on UPN. Almost nobody did - UPN was dying and everyone knew it. It was strange, UPN seemed to be a network so desperate that it would greenlight anything - but nobody ever watched anything but Star Trek. It's too bad, Home Movies is a very good and original show that does a style of humor that is supposed to be unanimatable. Animation is all about control and structure that looks loose and natural - much like Jazz. Genuinely unstructured things - like the highly improvised Home Movies or rock - are a threat to the core identity. Animation proved to be able to keep itself intact despite the worries, and so did jazz for that matter (is In A Silent Way the best fusion album? yes.). This was the show where we learned that H Jon Benjamin could not avoid being funny. I think the funniest interaction is when Melissa, self-appointed good girl that she is, respects the authority that Coach McGuirk technically has as both an adult and a soccer coach. McGuirk always manages to abuse this tiny smidgen of authority farther than one would think possible.

The Brak Show

This was the most direct spin-off of SG:C2C, which starred break out annoyance Brak. The Brak Show was ostensibly a parody of Leave It To Beaver, with Brak as Beev and Zorak as Wally. The joke was that Leave It To Beaver was an ancient relic long past parody even when this came out 15 years ago, so this was really just an exercise in being as extreme and bizarre as possible. Did it work? ... Sort of. The Brak Show was the most forgettable show on the line up. It wasn't as weird as Aqua Teen Hunger Force or extreme as Sealab 2021, it didn't mine a new kind of comedy like Home Movies or Harvey Birdman, it was just The Brak Show. Still, it was fun while it lasted, and I still sometimes end conversations with "some say he grew a beard and still lives here... But that's a damn lie!".

Aqua Teen Hunger Force

Aqua Teen Hunger Force was probably the worst show that night. It's not that it was horrible, ATHF just took a while to find the right formula. The first episode is still half pretending to be an adventure show, but soon they would start completely and wisely ignoring the title. The relationship between Shake and Frylock doesn't work as a result. Intelligent, magically empowered Frylock treats Shake as the leader because ... that's what the script says. Later episodes would get a more interesting dynamic - Shake would insist the script proclaims him leader, despite all evidence that it proclaims Frylock. This episode uses a bunch of backgrounds from the Powerpuff Girls pilot, which I found amusing at the time. I remember being disappointed that they didn't keep cannibalizing stuff from other Cartoon Network shows, like the Stooges used to do with Columbia sets. Maybe it was only funny to me.

Sealab 2021

Adam Reed and Matt Thompson's show Sealab 2021 is the secret father of modern comedy. I don't know if that is a compliment - have you seen modern comedy? I also know that the official father of modern comedy is The Simpsons, but years of alcohol abuse have left that show impotent. Sealab 2021 has an obvious parentage - it is Space Ghost: Coast To Coast's child. Space Ghost was weird, but rarely dark. Also, Space Ghost was a slow show, where comedy often came from beats rather than punchlines. No, the rapid-fire, dead baby, low artistic appeal comedy was invented right here in beautiful Sealab, Underwater. It was a breath of fresh water - I drowned laughing. Everyone was perfect. Even Erik Estrada was so funny that you could believe that he thought he was Erik Estrada De C.H.I.P.S. - just like Adam West fooled audiences into thinking he took Batman seriously. Family Guy went from doing Joyce DeWitt jokes to abortion jokes. The Simpsons abandoned comic tightness forever. Ugliness became holy writ. Sealab 2021 lasted too long and it knew it, but at its prime it was this strange, dark, hilarious joke machine.

Personal note: I own a Sealab 2020 board game. It is in America, though.

Space Ghost: Coast To Coast

The final Williams Street show was their classic - Space Ghost: Coast To Coast. I remember exactly which episode aired - "Knifin' Around" with Thom Yorke and Bjork. This is the series at its height, and "Knifin' Around" is the best episode of Space Ghost. Every line slays. "Those aren't children, they're packets of cream cheese.", "He's living on our couch, with the urine.", "I do this because ... I am special" and "We're just talking about ... dragons.". Bjork's innocence and Icelandinc confusion with the English language matches perfectly with Space Ghost's arrogance and inability to speak. Thom Yorke is monosyllabic, yet his dismissive "Yeah." or "No." are some of the episodes best and harshest reactions. Is Space Ghost's song on iTunes? "CutCutCutCutCutCutCutCutCutCutCut".

In retrospect, I should have gone to bed at this point. I had seen all the shows I wanted, including the best episode of Space Ghost that would ever be made. But, I stayed and watched and ... the next show was something special. The other shows were comedies, this was a drama. The other shows flaunted their negative production values, this one was gorgeous just on a technical level. The other shows had loose, ironic rhythms, this one kept a vice like grip on its pacing. The other shows had some background music if it felt like - often intentionally grating. This one put true musical art at the core of its existence. I've seen people talk about hearing The Beatles the first time, how it transformed them. For others, The Velvet Underground. For Patton Oswalt, it was Van Gogh's The Night Cafe. This was an artistic awakening being broadcast to unsuspecting teens. It is probable people even younger saw it and felt naughty for watching TV-14 shows. That was 15 years ago. The intended audience is now in it's mid-30's. Nine days later, the World Trade Center in New York, killing nearly 3,000 - by far the deadliest terrorist attack in history - instantly ushering in a new era in the most horrible possible way. Bebop, which was produced in 1998, has nothing to do with the mass death. But I wonder if any of the younger kids who watched this new, more mature show late at night and thousands of non-combatants immolated instantly had their world views darkened. Did the corrupt but beautiful world of Cowboy Bebop speak to young people who were overhearing the Bush Doctrine when their parents had control of the TV in the way the Beats spoke to the kids hearing the Truman Doctrine?

Maybe it was only me. Maybe I shouldn't have been shocked. After all, I had seen anime before, on Toonami for instance - but this was different. It wasn't a giant robot show or a martial arts contest. It was something new. And this great work, which became a genre unto itself was called

Cowboy Bebop

To bring back the original thread of this post, how did this very different kind of show get made? Cowboy Bebop is personal, groundbreaking, noncommercial and original - how did get on the air? We all know, though we don't like to admit, that most anime is an advertisement for other, more profitable media (toys, manga, etc.). Why did they let a man who had never helmed a show before make a show that would never ship merch? As you can imagine, it was an arduous journey and it almost didn't happen. Unfortunately, very little of this has been recorded. Despite super-director and creator Shinichiro Watanabe being every bit the equal of Hayao Miyazaki or Hideaki Anno, the latter two were only famous anime directors in Japan at the time. Even Anno, the protege of Miyazaki, with all his awards for Gunbuster (surely that won some awards? It's so awesome!), had to end the 80's with a Nadia, a bake-braking effort he was barred from bringing any originality - and was legally impossible to make a profit on. EVA, Macross Plus, and Ghost in the Shell all played an direct role in showing that hegemony was not necessary.

Macross Plus

To know how Cowboy Bebop got made, it's necessary to know a bit about its core creative personnel. The most important person behind Bebop was series director Shinichiro Watanabe. Earlier I said that he never helmed a series - this is actually only partially true. He had co-directed the instant classic Macross Plus, with Macross creator Shoji Kawamori, who also played several minor but important roles in Bebop as well (such as writing Speak Like A Child, one of the best episodes of television in any genre). I know little about Watanabe's pre-Macross career, and from what I have seen it doesn't seem like he was allowed particular creative leeway by Sunrise. I imagine that the animation is littered with geniuses that could reinvent animation if given the chance - and just as many fools who think they could. I don't begrudge Bandai for not giving him special treatment. Nobody knew.

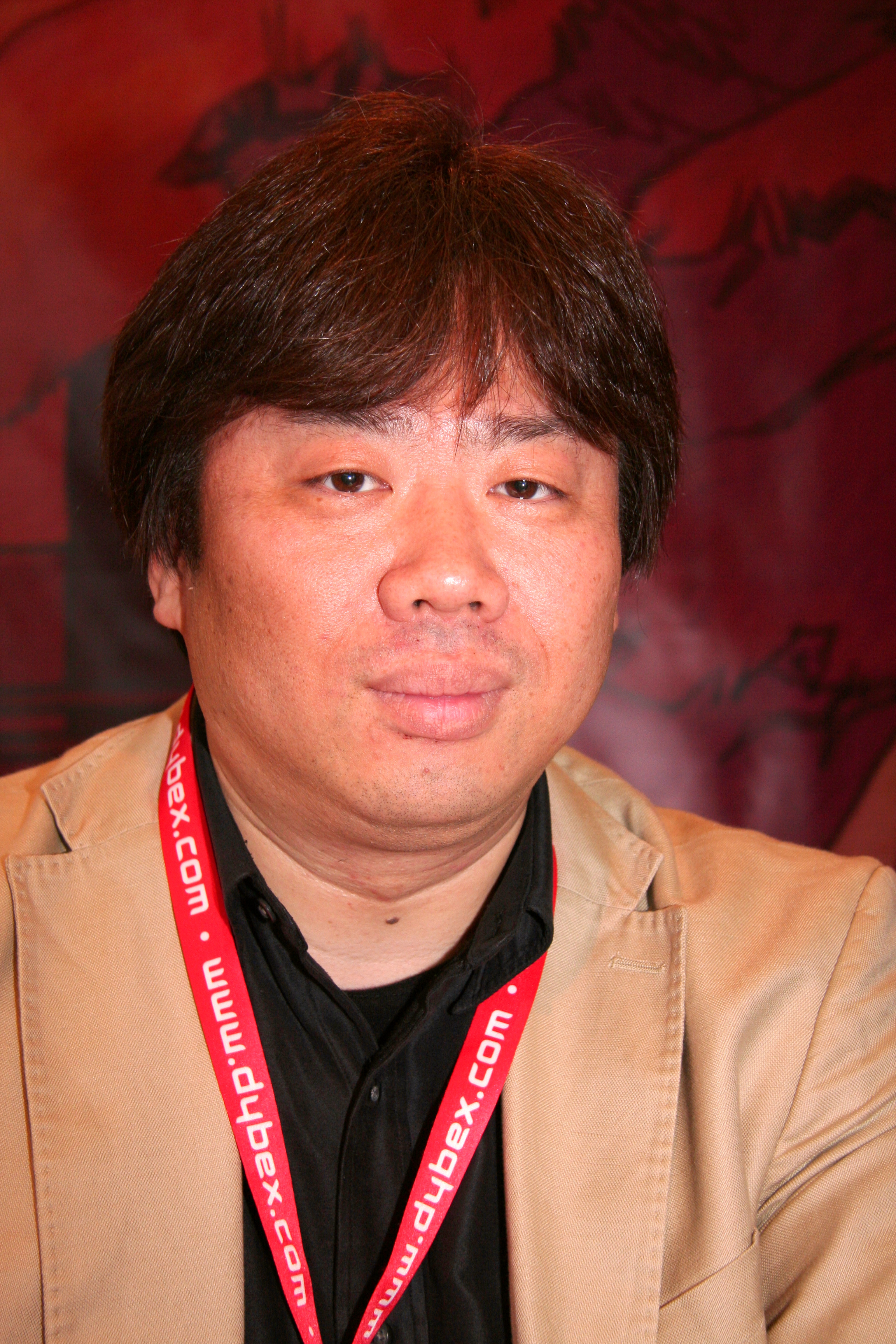

Shinichiro Watanabe

Watanabe was approached to make a series after the success of Macross Plus. Perhaps EVA, the weird new show that was climbing up the charts, was making studios aware of the idea of a creator driven series, but it was the marketing department of Bandai Visual that approached Watanabe with the idea. And what was the brilliant idea that the marketers came up with?

"Spaceships.".

As long as it had space ships, they said, they could sell toys and make a profit. And Watanabe was asked to bring that ... "idea" to the public. Watanabe made the show he wanted to make: a show where the main characters were down and out, a show where people drank, used drugs, got violent - even a show that included plenty of non-Japanese characters. He conceived of a two-part epic centered on a transgendered person. The marketing department was furious. "But", he explained, "It has spaceships!".

Cowboy Bebop was not picked up.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, Sunrise swooped in and offered him the chance to make the show if he could start right away. He was to be given a talk show push for the first episode and a prime spot on TV Tokyo. I don't know if anyone told him that he was replacing Kodocha, a show aimed at young girls, but I like to imagine that was kept in the dark. Production was still going on as the series began airing. As we get into the episodes, I'll talk more about the disastrous TV Tokyo run - suffice to say Watanabe was screwed by the network hard enough that he can say "Firefly who?".

Kodocha is actually really good, but ...

So, what is working with Watanabe like? For a guy whose style depends so heavily on tight timing, Watanabe runs a lax ship. I remember wunderkind composer Yoko Kanno description of the Bebop production:

"On most shows, everyone is always shouting. Stuff like, 'The hero should do this!' or 'The heorine would never say that!'. But on Bebop everyone was quiet. Sometimes I'd be looking for somebody and thinking 'Are these people actually at work?'."

Yoko Kanno

Speaking of Yoko Kanno, Macross Plus was also where Watanabe first worked with her, whose genre defying, kaledescopic music would play more than a major role in Bebop (trivia: actually worked with Kanno on the music of Macross Plus, to the point that Kanno didn't recognize Watanabe when they first met to work on Bebop!). Macross Plus put her on the map. The music crossed genres and reinvented idioms. It must have been brutal work - she did all the arranging and orchestrating herself.

Kanno did more than write the music for Cowboy Bebop, her playful spirit and incredible genius inspired Watanabe to retool one of the main characters, "Radical" Ed, to resemble her. Watanabe gave her enormous leeway. She was allowed even to question the writer and director's instructions as to what kind of music to compose. Suggesting that is a instant fire-worthy offense in a normal show. But Watanabe had that much faith in her skill. He was richly rewarded. World hopping Yoko Kanno called in a lot of favors (there are literally hundreds of musicians on the Cowboy Bebop soundtracks, many of whom were given creative roles) and gave Bebop the score of a movie many, many times its budget.

Yoko Kanno was a child prodigy. She began playing keyboard in kindergarten, where she organ behind hymns (she went to a Catholic school). Her parents encouraged her classical keyboard skill very early and she began participating in contests in second grade. In her memory, she was fiercely competitive as a child. The composer son of Ryunosuke Akutagawa (who wrote a little story called "Rashomon") was the first to give her the advice of avoiding pointless virtuosity. In middle and high school, she was in a brass band, where she 1) learned to arrange for brass and 2) developed a dislike of performing standards. She went to Waseda University to study literature (her idea of rebellion against the strict world of classical music), and for her summer break took a bus tour of the US to experience its music. I think that is why her music works so well for Bebop. For Kanno, Jazz and US music is world music. It makes sense to her to bring in more percussion. That world music/space music vibe makes the Bebop music unique even in the Jazz world it often draws from.

Keiko Nobumoto

Hey, who is this "writer" that Kanno felt she could musically overrule? That would be the incredibly talented Keiko Nobumoto, head writer for this series as well as Wolf's Rain and co-writer of Tokyo Godfathers. While extremely talented, Nobumoto is too slow for most producer's tastes, preventing her from developing a large filmography. On the other hand, it means everything she writes is impressive. On Bebop, she could count on Watanabe's confidence, but I'm sure the producers were pulling out their hair as the deadlines fast approached. She is one of the more mysterious of the creators, I can't find any interviews with her at all.

Toshihiro Kawamoto

Character designer Toshihiro Kawamoto was brought into the production after it was greenlit by Sunrise, so fairly late in the process. He also did most of the promotional artwork, so you know he's a very talented and stylish artist. In addition, his artbook is a key behind the scenes resource for me. I'll be talking about his approach to character design a lot, but I'll wait until the characters show up. Kawamoto would go on to found Studio BONES in 1998, using money earned from Cowboy Bebop The Movie with two other Bebop employees to create a more artist oriented studio. BONES made Space Dandy, which to me seems to return the favor.

Now that we have met much of the core creative team and reflected the way it came to me, it is obvious that only the third choice could work. I have to dive in and see Bebop myself. And I will...

Next time. See You Space Cowboys!

No comments:

Post a Comment