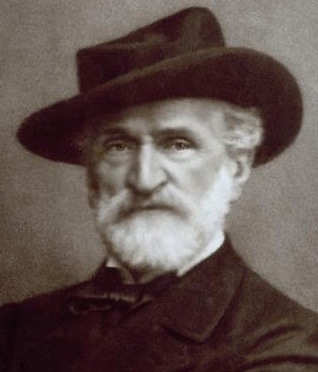

George Bernard Shaw in 1894, when he ended his regular music column

There are two sorts of persons: Platonists and Aristotleans. A Platonist is the sort that has an idea of how things ought to be, whether it is a piano recital or a state. As such, every movie, book, nation, planet and computer program could be perfect but imperfection in execution prevents it. The critic is always and everywhere a Platonist, while res publica are not a person. An Aristotlean is an impassive sort who prefers what he likes and avoids what he dislikes not on any scale but simply as the offers vary. Platonists dominate our discourse despite probably not dominating us numerically. The only chance that Aristotleanism is allowed to speak up is when someone wants to give a Platonist view of what a critic "ought to be" - they should be strict Aristoleans when they oppose me and powerful Platonists when they are with me.

This book, a collection of writings on music written by George Bernard Shaw - the mad genius of the Fabians - is full of the indignant Platonist howling that the loftiest love song of Mozart must vibrate through a stuffy prima donna's undeserving vocal chords. Such a collection is valuable for two reasons: First, because Shaw is equally comfortable analyzing, contextualizing and criticizing Mozart at his best as he is among the submucousal glands of the throat; Second, because Shaw is a great writer whose venom and sweetness would have value even if he used them like Pauline Kael (randomly and without accuracy).

Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart

Bernard Shaw claims multiple times in this book that he learned drama from music - from the evidence he gives this is likely true. But he worms music halfway to drama by having little patience for instrumental music. Shaw's interest is in singer/actors and his demands are rigorous: they must sing both Mozart and Wagner both perfectly and easily, they must show absolute selflessness by never requesting a bit of musical show off nor a bit of ham acting, they must always both mentally be in the scene artificed around them and of course they absolutely must have the same Platonic concept of the work as Shaw. Shaw, like most critics, can forgive any of the sins except the last.

I am of the opposite opinion, musically (and on a great deal besides). I think singing is somewhat annoying and doubt that any piece of singing longer than a few minutes could ever be worth hearing. Meanwhile, I could listen to hours of "absolute music" - as music without singing is so inaccurately called - without boredom. I have no interest in opera or music drama and positively dislike musicals.

When Shaw says "The music of the 18th century is all dance music", he speaks the truth as far as the sentence goes. But when he extends beyond this he finds that it must imply that all "absolute" music is without ideas. This is just misplaced concreteness. One might as well say that because books were originally written speeches they can contain no ideas. If we followed Shaw's rationalization to its end, the only piece of absolute music is Handel's "Water Music" - a bit of background music for some wealthy landlord. And maybe it is. If so, we need some new word for the work of Bach, Brahms or Duke Ellington.

Wilhelm Richard Wagner

Anyone for whom music is primarily a dramatic art form must believe that singing is the supreme art and composing lyrics for the voice the best possible poetry. Shaw, compelled by this logic, compares Shakespear (Shaw always spells the English Guillaume's name in this fashion) to Wagner to Shakespear's loss. When Juliet comes to stage to moon over Romeo she launches into a quite unrealistic mannered legalistic musing on the nature of names and naming. Shaw, who presumably has much experience in this area, tells us not what a young lady would do in this situation. Wagner, meanwhile, may have Isolde merely sing "Oh Tristan, Tristan, My Tristan, Tristan!" over and over again in pleasant metrical pattern. Much more realistic, says Shaw.

This is not a high standard for realism.

Shaw's dramatic music love is not just for drama but specifically German drama. For him, opera essentially begins with Gluck who taught the Italians not to bow to their prime donne and write appropriately dramatic music. The opera then reached its height with Mozart, for whom form and expression were as simple and affectationless as breath and defecation. Opera was then fortunately destroyed by Wagner, who - instead of worrying terribly about which chord followed what and smoothing out rhythms - simply played whatever music the poem called for at a moments notice. If this should be in D and that in E-Flat, so much the worse for D and E-flat.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi

Shaw's dislike for Italy is so deep that he has difficulty praising Verdi (incapable of writing for the voice) even as he grudgingly admits Falstaff is a masterpiece. This essay is a masterpiece in the form of "the critic angered by greatness". Nothing sets up the ire of the Platonist as the brilliant and successful pursuit of someone else's goals.

To give another example, it is obvious that Shaw's immense dislike of Rossini is a dislike not of Rossini's methods (which he disparages extensively and accurately) but of Rossini's goals. Rossini is writing neither for himself, musicians nor for thinkers but for that hideous abstraction "the common man". Shaw detects that Rossini thinks even less of the common man than even Shaw himself - this is more certainly more true and more damning than any technical detail Shaw hauls out.

Shaw in 1879, when he published his first novel

Shaw is an inveterate author, which is rather different from being a writer. He doesn't just fill up column space. Shaw is always noticing something concrete when listening to abstract music and deriving abstract thought from the concrete scenes. Anyone who has read The Perfect Wagnerite has seen the second but it is the first which occupies most of this volume. A trip to Bayreuth in 1894 brings pages of invective against the shoddy craftsmanship of German instruments and attacks on the competence of German singers (though he praises their instructors - the first essay makes clear why this seeming contradiction holds). As a result, Shaw is often most interesting when he leaves behind his subject. For instance, during an essay on Beethoven, he gives the best and only definition of jazz - "the old dance band, Beethoveniszed". This is no defect.

Shaw was - as a matter of course - completely mad. But he was also brilliant. This pose isn't a general review of his thought and writing. If I could take the time, I would recommend The Perfect Wagnerite, his brief but excellent Fabian Essays on economics, the 1938 movie Pygmalion and a bit of forgiveness for an old Irishman who wrote far too much & lived far too long.

Shaw On Music itself, meanwhile, is an excellent book for anyone with an interest in music, drama or the arts in general. In these cranky old essays I can detect the enthusiasm of the fan and lover despite the Platonistic personality burning through. Anyone who can read criticism for pleasure will enjoy this book, even if (like me) they have no interest in music-drama. People with an interest in "pop culture" reviews will also gain by this book, I think, because of its de-mystifying approach to works that are now considered classics. If you imagine a book of essays by the average music blogger who was also a Nobel Prize Winner in Literature, then you have a good estimate of what this book is like.

No comments:

Post a Comment