John Maynard Keynes

This is a post for all and none. Initiates to economics will see the fast one I'm trying to pull a mile a way, novices will have no idea what I'm blathering about. It's my attempt at writing a Nick Rowe post. I want to apologize in advance if I get the numbers wrong. The medium I'm using to write this is not conducive to editing and I am a poor enough craftsman to blame my tools. What I want to do is to make Keynes and monetarism strange to you again. Strange in the way it felt to Lionel Robbins and Jacob Viner in the 40's, when they were new. It won't be easy, since their language has pervaded thought so perfectly that it is hard to even talk without it...

Jacob Viner

A warning: Keynes was not different because he advocated spending out of depressions and saving out of inflations. Every sober person recommended this. Jacob Viner & Keynes on policy were indistinguishable - but there is no Vinerian economics. It is not because Keynes invented some black magic called "aggregation" - Giffen (yes, that Giffen) and his student Flux (who was the first to recognize Euler as the author of his famous theorem on homogeneous functions) had a spat on measuring national income a decade before the General Theory. Keynes was not different because he was a "statist" or because he was secretly had a labor theory of value or etc, etc, etc. The world was full of those types, but they didn't become Keynes. So what was it? Where to start...

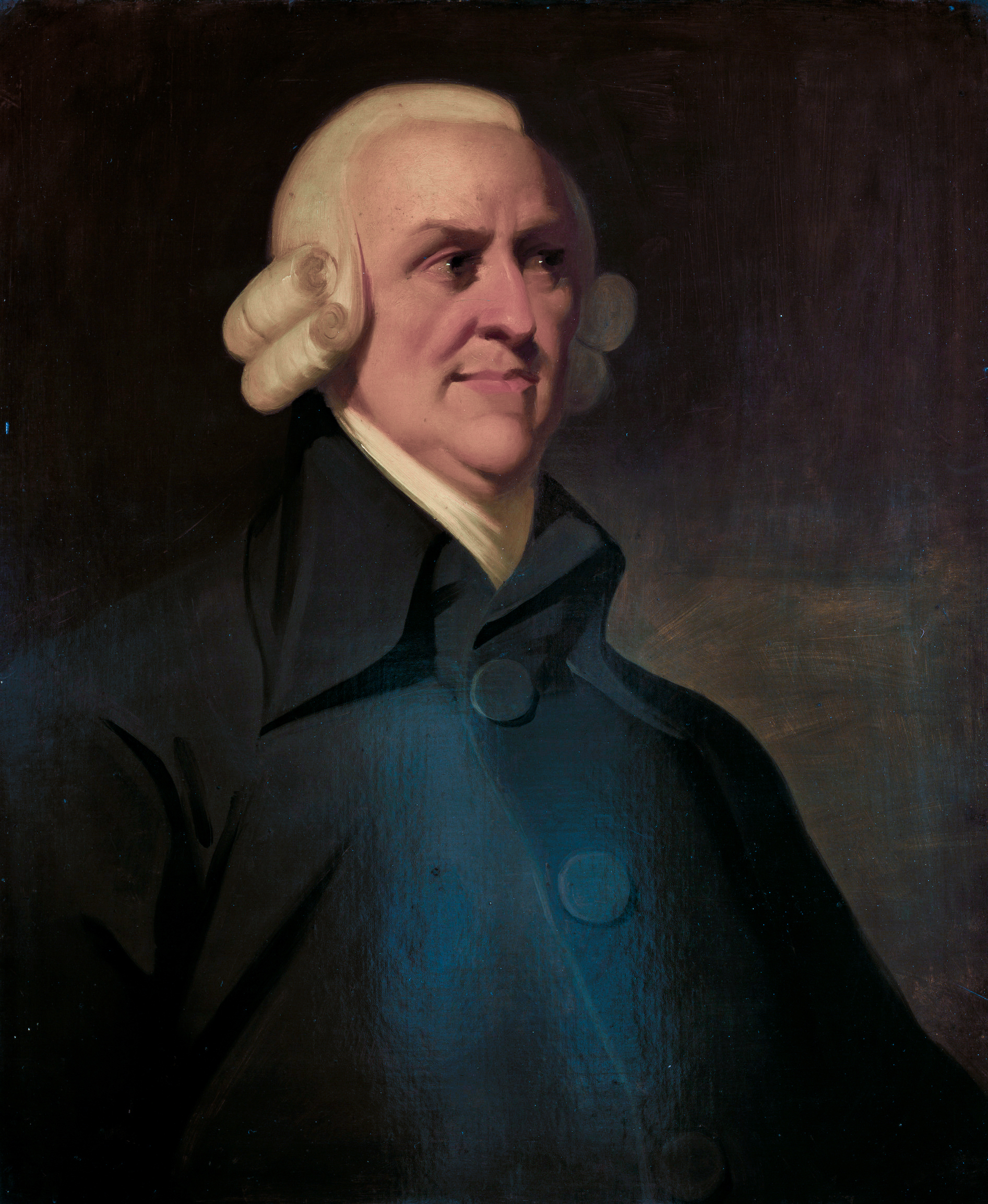

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a wise man as well as a great economist, a man who knew where to start things. Smith gave us the following "State Of Nature" argument, or just-so story:

"If among a nation of hunters, for example, it usually costs twice the labour to kill an eager which it does to kill a deer, one beaver should naturally exchange for or be worth two deer."

Isn't that lovely?

David Hume

Keynes - who was also a great and wise man whatever anyone tells you - did not start with a just-so story about the existence of trade and the balance of demands, though he probably should have. Unlike the other world changing theses of its era (such as Frank Knight's Risk, Uncertainty And Profit), his General Theory assumes that you walk in capable of doing marginal economics on the level of a Pigou off the bat rather than spending a chapter on his personal conception of the supply and demand lines. As a matter of historical fact, Keynes never wrote a introductory book on basic conceptions (he and Pigou would just say "It's all in Marshall."!). Most of his serious writing is on money on the international stage, but the General Theory is about an "Isolated State", as it were. This might explain why students and the unserious had such difficulty but it wasn't just them...

We have to keep going past Adam Smith now. Here comes Irving Fisher, perhaps the greatest economist of all time ... though not gifted with deep personal wisdom. His American accent will be more familiar than Smith's 18th century Scottish brogue. He asks us to consider not hunting today, but hunting tomorrow as well. Let's say that a deer in the hand is worth two in the bush. How many deer today is a beaver tomorrow worth? The answer must be four - a beaver is worth two deer and a tomorrow is worth half a today.

But what if the difficulty of hunting changes with the seasons? Let's say that hunting is easier next season, so that the same amount of labor that gets one beaver today will also get two deer tomorow, three beaver tomorrow or four deer tomorrow. Then a promise of a deer tomorrow is worth half a deer today, the promise of a beaver tomorrow is worth a third of a deer today and the promise of a beaver tomorrow is worth 3/2 of a deer today. In terms of marginal analysis, this is the product rule for derivatives applied to a simple spot & future market. If the market left this so-called "intertemporal equilibrium", then anyone could gain just by cyclically trading beaver & deer. This arbitrage argument is in Keynes's General Theory (Chapter 17, part II).

So far, so good. Right now we're telling the story that Brad DeLong calls The Story Of The 20th Century - that of production increases & galloping scientific innovation. Economics is a serious subject about the things of our lives - the clean water, the iPhones and the clothes all together. Knight, Hayek and Schumpeter see that the entrepreneur is the central actor, able to take on uninsurable risks because they have local knowledge that others can't get - and the romantic temperament that drives the will to power. And this is - as far as it goes - undeniably true.

But it doesn't go all the way. The ancients called wise he who can control his enemies - and Keynes was a wise guy as well as a great man. The name The General Theory Of Employment, Interest And Money was a trick but not an underhanded one. It is that, but this isn't mainly that. The book is really an exposition of a Money Theory Of Production. Keynes announced such a book before writing it and admits it in the aforementioned Chapter 17.

Knight and Viner - the Old Men of Chicago - obsessed over the poorly named concept of the "long run". What this really means is that the path of production is picked out more or less like the beavers and the deer above, except lucky years are replaced by lucky (or, rarely, talented) entrepreneurs. In modern terms, this is called "golden path growth" and the obsession is justified by "turnpike theorems". But Keynes, the greatest of the international monetary theorists and practitioners, saw that in many countries unbalanced flow & pricing of gold destroyed industries even though they were stocked to the gills with gutsy entrepreneurs and genius scientists.

Why, back with our hunters, do you think that just because they can get the deer and beaver at the rates quoted they necessarily will? Must every hunter go out for the hunt? This is a very crude way of thinking about "output in general". Surely a hunter could become irrationally exuberant (filled with romance, let's say) about his ability to kill beaver and hunt it in defiance of logic - and surely this would alter the price ratio whether he gets lucky or not. Surely each level of output, in terms of labor spent, is associated with a particular price system - in economic terms, each quantity of labour to spend gives a different production possibility frontier which, as it's dragged out doesn't necessarily touch the indifference curve at a locus of points drawing a straight line.

That's 2deep4me. Let's hear one last folk tale instead. Next year doesn't make it easier to hunt in general. Instead, next year the amount of labor to catch a beaver will be four times what it takes to hunt a deer tomorrow - and that amount will stay static. Now nobody would buy a promise for a deer tomorrow at a market clearing price. The asset whose rate of production has climbed most rapidly with output in general has knocked out the other assets - exactly as Keynes taught in Chapter 17!

You might be thinking "Where's the unemployment, the interest rates & the money?". They're all there. The fast one I pulled is to talk about the path of production instead of the "interest rate". Interest rates are an abstraction, what exists are things and prices. Only after acclimatization in the polite fiction of interest rates does the intertemporal & Keynesian world make obvious sense. If I had said "The money-rate of interest rules the roost." one would be off talking about unrelated things. But when I say the identical, but differently worded "The production path of money knocks out less profitable production paths." it suddenly feels alien, requiring proof and argument. Which is what Keynes did.

Keynes ruined economists lives in order to save civilians. Before Keynes, all economists agreed that just because the story of the 20th century was about innovation and not money it should be the story that economists tell. Schumpeter the romantic was so furious that he said that if Keynes would not tell this story he wasn't an economist at all! It seemed so obvious that economists must focus on The Story, right? Keynes made economists not the epic poets of innovation but mere dentists checking Ulysses teeth before he goes to war.

But what if the difficulty of hunting changes with the seasons? Let's say that hunting is easier next season, so that the same amount of labor that gets one beaver today will also get two deer tomorow, three beaver tomorrow or four deer tomorrow. Then a promise of a deer tomorrow is worth half a deer today, the promise of a beaver tomorrow is worth a third of a deer today and the promise of a beaver tomorrow is worth 3/2 of a deer today. In terms of marginal analysis, this is the product rule for derivatives applied to a simple spot & future market. If the market left this so-called "intertemporal equilibrium", then anyone could gain just by cyclically trading beaver & deer. This arbitrage argument is in Keynes's General Theory (Chapter 17, part II).

Frederich Hayek

So far, so good. Right now we're telling the story that Brad DeLong calls The Story Of The 20th Century - that of production increases & galloping scientific innovation. Economics is a serious subject about the things of our lives - the clean water, the iPhones and the clothes all together. Knight, Hayek and Schumpeter see that the entrepreneur is the central actor, able to take on uninsurable risks because they have local knowledge that others can't get - and the romantic temperament that drives the will to power. And this is - as far as it goes - undeniably true.

But it doesn't go all the way. The ancients called wise he who can control his enemies - and Keynes was a wise guy as well as a great man. The name The General Theory Of Employment, Interest And Money was a trick but not an underhanded one. It is that, but this isn't mainly that. The book is really an exposition of a Money Theory Of Production. Keynes announced such a book before writing it and admits it in the aforementioned Chapter 17.

Knight and Viner - the Old Men of Chicago - obsessed over the poorly named concept of the "long run". What this really means is that the path of production is picked out more or less like the beavers and the deer above, except lucky years are replaced by lucky (or, rarely, talented) entrepreneurs. In modern terms, this is called "golden path growth" and the obsession is justified by "turnpike theorems". But Keynes, the greatest of the international monetary theorists and practitioners, saw that in many countries unbalanced flow & pricing of gold destroyed industries even though they were stocked to the gills with gutsy entrepreneurs and genius scientists.

Why, back with our hunters, do you think that just because they can get the deer and beaver at the rates quoted they necessarily will? Must every hunter go out for the hunt? This is a very crude way of thinking about "output in general". Surely a hunter could become irrationally exuberant (filled with romance, let's say) about his ability to kill beaver and hunt it in defiance of logic - and surely this would alter the price ratio whether he gets lucky or not. Surely each level of output, in terms of labor spent, is associated with a particular price system - in economic terms, each quantity of labour to spend gives a different production possibility frontier which, as it's dragged out doesn't necessarily touch the indifference curve at a locus of points drawing a straight line.

That's 2deep4me. Let's hear one last folk tale instead. Next year doesn't make it easier to hunt in general. Instead, next year the amount of labor to catch a beaver will be four times what it takes to hunt a deer tomorrow - and that amount will stay static. Now nobody would buy a promise for a deer tomorrow at a market clearing price. The asset whose rate of production has climbed most rapidly with output in general has knocked out the other assets - exactly as Keynes taught in Chapter 17!

You might be thinking "Where's the unemployment, the interest rates & the money?". They're all there. The fast one I pulled is to talk about the path of production instead of the "interest rate". Interest rates are an abstraction, what exists are things and prices. Only after acclimatization in the polite fiction of interest rates does the intertemporal & Keynesian world make obvious sense. If I had said "The money-rate of interest rules the roost." one would be off talking about unrelated things. But when I say the identical, but differently worded "The production path of money knocks out less profitable production paths." it suddenly feels alien, requiring proof and argument. Which is what Keynes did.

Joseph Schumpeter

Keynes ruined economists lives in order to save civilians. Before Keynes, all economists agreed that just because the story of the 20th century was about innovation and not money it should be the story that economists tell. Schumpeter the romantic was so furious that he said that if Keynes would not tell this story he wasn't an economist at all! It seemed so obvious that economists must focus on The Story, right? Keynes made economists not the epic poets of innovation but mere dentists checking Ulysses teeth before he goes to war.